Yule, Yuletide, and Its Historic Roots

Yule has deep historical roots woven into the fabric of Germanic and Norse cultures, marking a significant celestial event and heralding the arrival of the winter solstice. In these ancient societies, Heathens celebrated Yule as a pivotal festival during the darkest time of the year. Yule symbolizes the rebirth of the sun and the promise of brighter days ahead.

Yule has deep historical roots woven into the fabric of Germanic and Norse cultures, marking a significant celestial event and heralding the arrival of the winter solstice. In these ancient societies, Heathens celebrated Yule as a pivotal festival during the darkest time of the year. Yule symbolizes the rebirth of the sun and the promise of brighter days ahead.

Germanic Origins

Winter Solstice Celebration

Germanic tribes honored the winter solstice in the form of the Yule festival. Yule commemorates the moment when the sun, which had been growing weaker and lower in the sky, reaches its lowest point and then began its ascent. Yule promises the return of longer days.

Germanic tribes honored the winter solstice in the form of the Yule festival. Yule commemorates the moment when the sun, which had been growing weaker and lower in the sky, reaches its lowest point and then began its ascent. Yule promises the return of longer days.

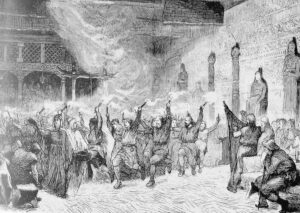

Feasting and Merriment

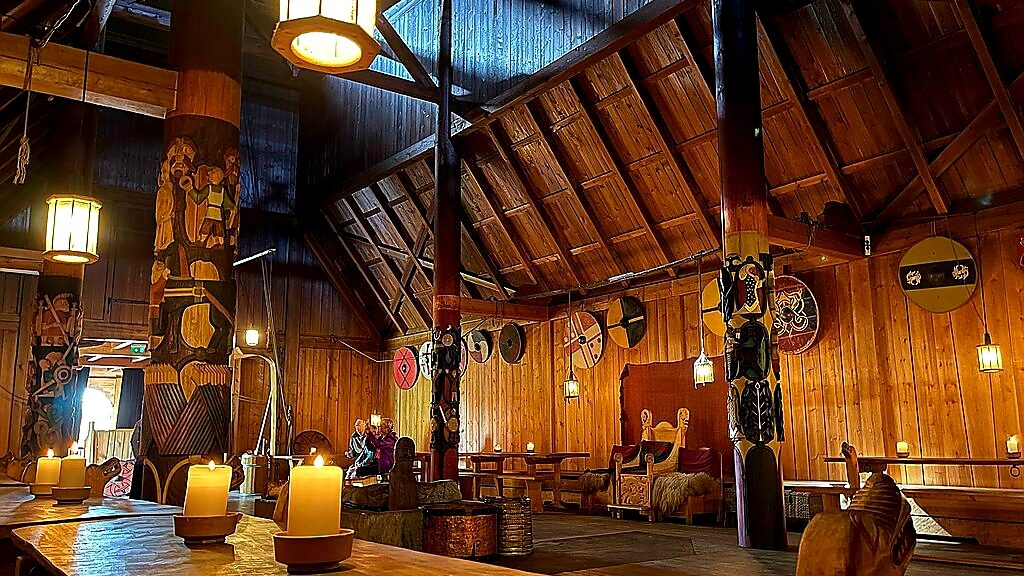

Yule celebrations were marked by feasting and revelry, with communal gatherings to share food, drink, and festivities. The feast was a central aspect, symbolizing the abundance of the harvest and the hopes for a prosperous year ahead.

Yule Log Ritual

The Yule log held great significance. A large, specially selected log was ceremoniously brought into the home and burned in the hearth for the duration of the festival. It represented the continuity of life, warmth, and protection against malevolent spirits during the long winter nights.

Norse Traditions

Norse Mythology and Yuletide

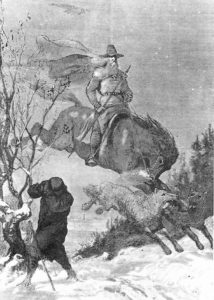

In Norse mythology, the festival of Yule, known as “Jól,” includes the legends of Odin, the Allfather, and the Wild Hunt. Odin, whom we associate with wisdom, war, and poetry, leads the Wild Hunt across the skies during the Yuletide. The Wild Hunt is a spectral procession of warriors and magical beings.

In Norse mythology, the festival of Yule, known as “Jól,” includes the legends of Odin, the Allfather, and the Wild Hunt. Odin, whom we associate with wisdom, war, and poetry, leads the Wild Hunt across the skies during the Yuletide. The Wild Hunt is a spectral procession of warriors and magical beings.

Twelve Days of Yule

The Norse celebrated Yule over twelve days, a period known as “The Twelve Nights.” Each night represented one month of the upcoming year, foretelling events and omens for the months ahead.

Gift-Giving and Symbolism

Yule was a time for gift-giving among the Norse, symbolizing goodwill and fostering relationships. These gifts often held symbolic meanings, representing blessings for the coming year or tokens of appreciation.

Honoring Yule Today

Modern Heathens seek to honor the traditions of their ancestors while adapting them to fit contemporary lifestyles. Celebrating Yule in a way that echoes the ancient Germanic and Norse practices can be a meaningful endeavor. Here are some ways Heathens might celebrate Yule today.

Yule Blot and Rituals

Blot Ritual

Conduct a Yule Blot, a sacrificial offering ceremony to honor the gods and spirits. Offerings could include mead, ale, or food. Place them in a sacred space or outdoors, accompanied by prayers or spoken words of gratitude and intention.

Conduct a Yule Blot, a sacrificial offering ceremony to honor the gods and spirits. Offerings could include mead, ale, or food. Place them in a sacred space or outdoors, accompanied by prayers or spoken words of gratitude and intention.

Honoring the Ancestors

Dedicate part of the celebration to honoring ancestors. Set up an altar with pictures or symbols representing ancestors. Offer them food, drink, or light candles in their memory, acknowledging their influence and seeking their blessings for the coming year.

Feasting and Hospitality

Yule Feast

Host a grand feast with friends and family, emphasizing traditional foods that the ancestors might have been eaten. Foods include roasted meats, root vegetables, bread, and mulled drinks. Consider using local, seasonal ingredients as a nod to ancestral agricultural practices.

Community and Hospitality

Emphasize hospitality by inviting others to share in the festivities. Open your home to friends, neighbors, or members of the Heathen community to foster camaraderie and a sense of shared celebration.

Rituals and Symbolism

Lighting the Yule Log

Light a special Yule log in the fireplace or bonfire outdoors to symbolize the warmth and light returning to the world. Decorate the log with runes, symbols, or herbs with significant meanings.

Evergreen Decorations

Deck the halls with evergreen boughs, holly, or mistletoe. These plants held symbolic significance for ancient Heathens, representing endurance, protection, and fertility.

Divination and Reflection

Reflective Practices

Take time for introspection, reflecting on the past year and setting intentions for the year ahead. Use divination tools such as runes to seek guidance or insights for the coming months.

Storytelling and Lore

Share tales from Norse mythology or stories of Yule traditions with family and friends, passing down cultural lore and fostering a deeper connection to ancestral wisdom.

Share tales from Norse mythology or stories of Yule traditions with family and friends, passing down cultural lore and fostering a deeper connection to ancestral wisdom.

By blending these ancient customs with a modern approach, Heathens can create meaningful and authentic Yule celebrations that pay homage to their ancestors while embracing the spirit of renewal, community, and the changing seasons. Adaptation and personal interpretation play key roles in shaping Yule celebrations for Heathens today, allowing for a vibrant continuation of these age-old traditions.

In both Germanic and Norse cultures, Yule was a time of deep spiritual significance, emphasizing the cyclical nature of life, the turning of the seasons, and the hope for renewal. These ancient traditions and customs, rooted in the observation of the winter solstice, continue to resonate in modern-day interpretations of the Yule festival within contemporary Heathenry and Pagan practices.

Happy Yule!!

Did you know you can become my patron for as little as $5 a month? This entitles you to content not posted anywhere else. Plus you get to see posts like this three days before the public! Without patrons, I’d be having a very hard time keeping this blog going. Become a patron today!Become a Patron!

Dísablót is a celebration of female ancestors, or Dísir, is the major holiday that begins Skerpla, usually on May 14th. People celebrated this holiday with feasting and singing. The Dísir, like the Alfar, are considered powerful guardians–some even becoming goddesses. Since they are female ancestors, people offer blóts, usually of food and mead. I wrote a

Dísablót is a celebration of female ancestors, or Dísir, is the major holiday that begins Skerpla, usually on May 14th. People celebrated this holiday with feasting and singing. The Dísir, like the Alfar, are considered powerful guardians–some even becoming goddesses. Since they are female ancestors, people offer blóts, usually of food and mead. I wrote a

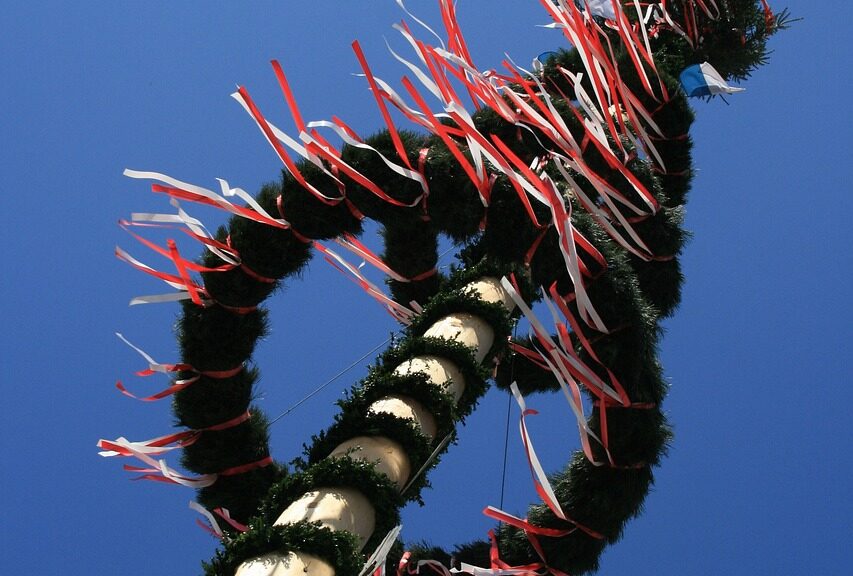

Walpurgis Night and May Day are two festivals that are steeped in pagan and Heathen traditions. People have celebrated them for centuries in various parts of Europe. These festivals mark the beginning of the summer season. Both pagans and Christians associate these holidays with fertility, growth, and renewal.

Walpurgis Night and May Day are two festivals that are steeped in pagan and Heathen traditions. People have celebrated them for centuries in various parts of Europe. These festivals mark the beginning of the summer season. Both pagans and Christians associate these holidays with fertility, growth, and renewal.

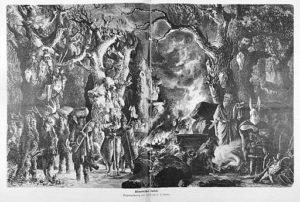

During Valpurgisnacht, people would light bonfires and leave offerings of food and drink for their ancestors and other spirits. They would also dress up in costumes and masks to scare away evil spirits.

During Valpurgisnacht, people would light bonfires and leave offerings of food and drink for their ancestors and other spirits. They would also dress up in costumes and masks to scare away evil spirits. May Day, which is celebrated on May 1st, is another festival that has roots in pagan and Heathen traditions. The festival marks the beginning of the summer season, and people associate it with fertility, growth, and the renewal of life after the long winter months.

May Day, which is celebrated on May 1st, is another festival that has roots in pagan and Heathen traditions. The festival marks the beginning of the summer season, and people associate it with fertility, growth, and the renewal of life after the long winter months. Walpurgis Night and May Day are both festivals that are steeped in pagan and Heathen beliefs. They show a deep reverence for nature and the cycles of life.

Walpurgis Night and May Day are both festivals that are steeped in pagan and Heathen beliefs. They show a deep reverence for nature and the cycles of life.

Welcome, fellow Heathens, to the month of Harpa or Gaukamánuður. In modern times, this month roughly corresponds with the middle of April and marks the arrival of spring. In Old Norse tradition, Harpa was a time of celebration and renewal. People celebrated because winter gave way to the sun’s warmth and spring’s return.

Welcome, fellow Heathens, to the month of Harpa or Gaukamánuður. In modern times, this month roughly corresponds with the middle of April and marks the arrival of spring. In Old Norse tradition, Harpa was a time of celebration and renewal. People celebrated because winter gave way to the sun’s warmth and spring’s return.

During the month of Harpa, the Vikings celebrated the sun’s return and the longer days. In Norse mythology, the sun is personified as the goddess Sunna, who rides across the sky in a horse-drawn chariot. The Vikings celebrated the return of the sun with festivals and rituals.

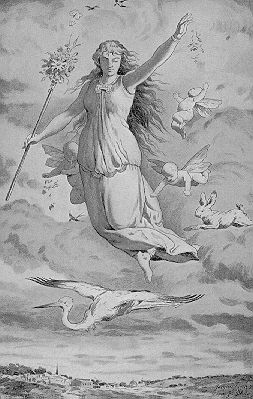

During the month of Harpa, the Vikings celebrated the sun’s return and the longer days. In Norse mythology, the sun is personified as the goddess Sunna, who rides across the sky in a horse-drawn chariot. The Vikings celebrated the return of the sun with festivals and rituals. During the Blót, offerings of eggs and flowers were also made to the goddess Eostre, as eggs symbolized new life and flowers represented the beauty of nature. The festival of Eostre was also associated with the Christian holiday of

During the Blót, offerings of eggs and flowers were also made to the goddess Eostre, as eggs symbolized new life and flowers represented the beauty of nature. The festival of Eostre was also associated with the Christian holiday of

Another way to celebrate the month of Harpa is to hold a bonfire or other outdoor gathering with friends and family. You can gather around the fire, share food and drink, and tell stories or sing songs that connect you with the natural world. You may also wish to perform a ritual or make offerings to the land spirits, asking for their blessings on the coming season.

Another way to celebrate the month of Harpa is to hold a bonfire or other outdoor gathering with friends and family. You can gather around the fire, share food and drink, and tell stories or sing songs that connect you with the natural world. You may also wish to perform a ritual or make offerings to the land spirits, asking for their blessings on the coming season.

Sowilo or Sowelu, also known as Sol or Sigel, is the sixteenth rune of the

Sowilo or Sowelu, also known as Sol or Sigel, is the sixteenth rune of the  Like all runes, Sowelu can be used for divination. There are a few different methods for reading runes, but one common method is to draw three runes and interpret them as past, present, and future.

Like all runes, Sowelu can be used for divination. There are a few different methods for reading runes, but one common method is to draw three runes and interpret them as past, present, and future.

Skadi is a Norse goddess who embodies the power of winter, hunting, and skiing. She is one of the most fascinating and complex goddesses in Norse mythology. Skadi’s name means “shadow” or “shade,” which reflects her mysterious and enigmatic nature.

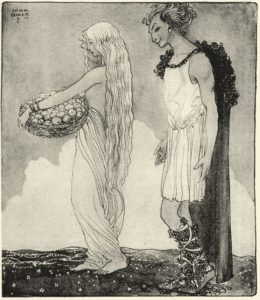

Skadi is a Norse goddess who embodies the power of winter, hunting, and skiing. She is one of the most fascinating and complex goddesses in Norse mythology. Skadi’s name means “shadow” or “shade,” which reflects her mysterious and enigmatic nature. Skadi’s story is one of revenge, power, and redemption. According to Norse mythology, Loki killed Skadi’s father, Thiazi. Thiazi kidnapped Loki, forcing the trickster god to lure Idunn and her golden apples away from Asgard so Thiazi could kidnap her. The golden apples gave the gods immortality, so they made Loki rescue Idunn and her apples. In his escape, Loki kills Thiazi.

Skadi’s story is one of revenge, power, and redemption. According to Norse mythology, Loki killed Skadi’s father, Thiazi. Thiazi kidnapped Loki, forcing the trickster god to lure Idunn and her golden apples away from Asgard so Thiazi could kidnap her. The golden apples gave the gods immortality, so they made Loki rescue Idunn and her apples. In his escape, Loki kills Thiazi. Skadi and Njord’s differing lifestyles and interests caused tension in their relationship. In retrospect, this difference is quite apparent. Skadi loved the mountains and the snow, while Njord preferred the cold and waves of the sea. They eventually separated, but not before Skadi had learned to appreciate the beauty of the sea and Njord had learned to appreciate the ruggedness of the mountains.

Skadi and Njord’s differing lifestyles and interests caused tension in their relationship. In retrospect, this difference is quite apparent. Skadi loved the mountains and the snow, while Njord preferred the cold and waves of the sea. They eventually separated, but not before Skadi had learned to appreciate the beauty of the sea and Njord had learned to appreciate the ruggedness of the mountains.

All right, buckle up, fellow pagans and Heathens, because it’s time to talk about the elephant in the room: Easter. You know, that holiday where Christians celebrate the resurrection of their lord and savior Jesus Christ by painting eggs, eating chocolate bunnies, and hiding baskets of treats for their kids? Yeah, that one.

All right, buckle up, fellow pagans and Heathens, because it’s time to talk about the elephant in the room: Easter. You know, that holiday where Christians celebrate the resurrection of their lord and savior Jesus Christ by painting eggs, eating chocolate bunnies, and hiding baskets of treats for their kids? Yeah, that one.

But let’s move on to some of the more tangible trappings of Easter. Eggs, for example. The egg is a potent symbol of fertility and new life in many cultures. Eggs have been used in springtime celebrations for thousands of years.

But let’s move on to some of the more tangible trappings of Easter. Eggs, for example. The egg is a potent symbol of fertility and new life in many cultures. Eggs have been used in springtime celebrations for thousands of years. Let’s now look at the Easter bunny. This fluffy little creature has nothing to do with the resurrection of Jesus Christ, but everything to do with the pagan celebration of spring. In Germanic folklore, the hare was associated with the goddess Ēostre, and was seen as a symbol of fertility and new life. The tradition of the Easter bunny laying eggs (yes, you read that right) is thought to have originated in Germany, where children would make nests for the hare to lay its eggs in.

Let’s now look at the Easter bunny. This fluffy little creature has nothing to do with the resurrection of Jesus Christ, but everything to do with the pagan celebration of spring. In Germanic folklore, the hare was associated with the goddess Ēostre, and was seen as a symbol of fertility and new life. The tradition of the Easter bunny laying eggs (yes, you read that right) is thought to have originated in Germany, where children would make nests for the hare to lay its eggs in.