The Norse Calendar: Skerpla – The Month of Brightness and Clearness

The month of Skerpla roughly corresponds to our modern month of May. It was the second month of the summer season. Here we’ll explore the historical and mythological significance of Skerpla. You’ll also learn why it was important for the Norse pagan communities.

What is Skerpla?

Skerpla was a month in the Old Norse calendar that marked the transition from spring to summer. Arguably, the name Skerpla may mean “brightness” or “clearness,” and some scholars think it refers to the increasing light and longer days of the summer season. During Skerpla, the days would become noticeably longer, and the sun would rise earlier and set later.

Skerpla in the Old Norse Calendar

The Old Norse calendar had a unique way of dividing the year into distinct seasons and months. The Norse divided their calendar into two main seasons: winter and summer. They divided winter into six months, which roughly corresponds to October, November, December, January, February, and March. They also divided summer into six months, which roughly corresponds to April, May, June, July, August, and September.

Each month in the Old Norse calendar has its own unique name, which came from the seasonal or agricultural activities that took place during that time of year. Skerpla was the second month of the summer season. It was when people would prepare their farms and fields for planting and cultivation.

Skerpla was when the days grew longer and the weather grew warmer. During Skerpla, people celebrated the return of life and growth to the land, and honored the gods and goddesses who presided over fertility, agriculture, and nature. This month also had the names stekktíð and eggtíð, meaning lambing time and egg time. The Norse, who were predominantly an agrarian society, named their months after the specific periods during which various farming tasks were carried out.

Skerpla in Norse Mythology

Skerpla was an important month in Norse mythology, and it was associated with several gods and goddesses who influence the natural world and the changing of the seasons.

Freyja is one of the most important goddesses of Norse mythology. People associate her with fertility, love, and beauty. Freyja is a goddess of the earth and the natural world, and she is associated with the growing and harvesting of crops.

The goddess Sif is also associated with Skerpla, and she is believed to be a goddess of agriculture and the harvest. Sif is the wife of the god Thor, and she is known for her long, golden hair, which is believed to represent the golden fields of grain that farmers planted.

In addition to the gods and goddesses, this month is also associated with a number of other mythical beings and creatures. The most famous of these are the alfar, or elves, who are believed to inhabit the natural world and possess magical powers.

Holidays and Celebrations

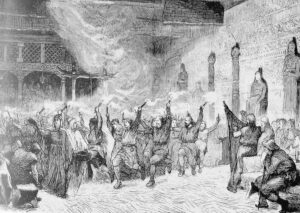

There is one holiday and celebration that took place during Skerpla, which is marked by feasting, dancing, and other forms of merrymaking. The Norse called it Dísablót, and it was a very important celebration.

Dísablót is a celebration of female ancestors, or Dísir, is the major holiday that begins Skerpla, usually on May 14th. People celebrated this holiday with feasting and singing. The Dísir, like the Alfar, are considered powerful guardians–some even becoming goddesses. Since they are female ancestors, people offer blóts, usually of food and mead. I wrote a piece about Dísablót HERE.

Dísablót is a celebration of female ancestors, or Dísir, is the major holiday that begins Skerpla, usually on May 14th. People celebrated this holiday with feasting and singing. The Dísir, like the Alfar, are considered powerful guardians–some even becoming goddesses. Since they are female ancestors, people offer blóts, usually of food and mead. I wrote a piece about Dísablót HERE.

Importance of Skerpla

Skerpla was an important month for the Norse and Norse pagan communities, as it marked the beginning of the agricultural season. During this month, people would prepare their fields and plant their crops. It was a busy time for everyone because the work done now would eventually lead to food for the winter.

Skerpla was an important month for our ancestors. It was a time of transition and change, as the days grew longer and the weather grew warmer. People celebrated the return of life and growth to the land, and honored the gods and goddesses who presided over fertility, agriculture, and nature. Skerpla was a time when people would come together to celebrate the abundance of the earth and the changing of the seasons.

—

Did you know you can become my patron for as little as $5 a month? This entitles you to content not posted anywhere else. Plus you get to see posts like this three days before the public! Without patrons, I’d be having a very hard time keeping this blog going. Become a patron today!Become a Patron!

Welcome, fellow Heathens, to the month of Harpa or Gaukamánuður. In modern times, this month roughly corresponds with the middle of April and marks the arrival of spring. In Old Norse tradition, Harpa was a time of celebration and renewal. People celebrated because winter gave way to the sun’s warmth and spring’s return.

Welcome, fellow Heathens, to the month of Harpa or Gaukamánuður. In modern times, this month roughly corresponds with the middle of April and marks the arrival of spring. In Old Norse tradition, Harpa was a time of celebration and renewal. People celebrated because winter gave way to the sun’s warmth and spring’s return.

During the month of Harpa, the Vikings celebrated the sun’s return and the longer days. In Norse mythology, the sun is personified as the goddess Sunna, who rides across the sky in a horse-drawn chariot. The Vikings celebrated the return of the sun with festivals and rituals.

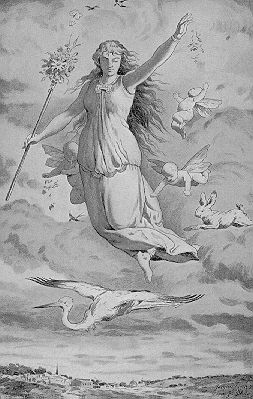

During the month of Harpa, the Vikings celebrated the sun’s return and the longer days. In Norse mythology, the sun is personified as the goddess Sunna, who rides across the sky in a horse-drawn chariot. The Vikings celebrated the return of the sun with festivals and rituals. During the Blót, offerings of eggs and flowers were also made to the goddess Eostre, as eggs symbolized new life and flowers represented the beauty of nature. The festival of Eostre was also associated with the Christian holiday of

During the Blót, offerings of eggs and flowers were also made to the goddess Eostre, as eggs symbolized new life and flowers represented the beauty of nature. The festival of Eostre was also associated with the Christian holiday of

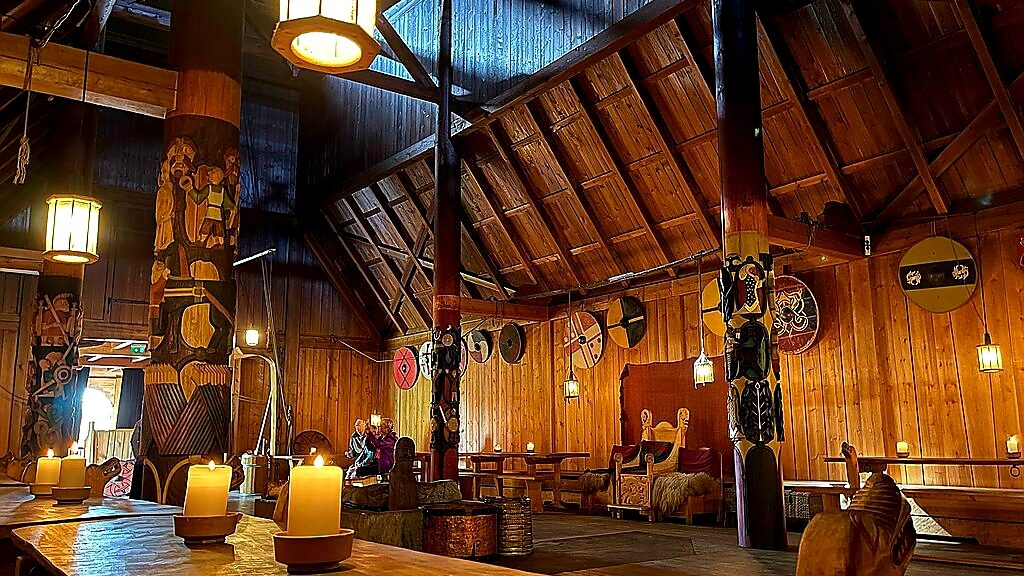

Another way to celebrate the month of Harpa is to hold a bonfire or other outdoor gathering with friends and family. You can gather around the fire, share food and drink, and tell stories or sing songs that connect you with the natural world. You may also wish to perform a ritual or make offerings to the land spirits, asking for their blessings on the coming season.

Another way to celebrate the month of Harpa is to hold a bonfire or other outdoor gathering with friends and family. You can gather around the fire, share food and drink, and tell stories or sing songs that connect you with the natural world. You may also wish to perform a ritual or make offerings to the land spirits, asking for their blessings on the coming season.

Nowadays we have refrigeration, which is possibly why Gormánuður may be puzzling to some of you. After all, we can get meat year round and keep it in the freezer or refrigerator. And you’re probably quite aware that our ancestors didn’t have refrigeration until 1913–not that long ago–available for home use. Even then, owning a home refrigerator was expensive and it didn’t become popular until the 1930s. So, your recent ancestors probably had iceboxes–that is actual boxes that held ice to keep their food fresh. The icebox was invented and patented by a farmer in 1802. The original icebox was made from wood, rabbit skins, and lots of ice (duh!). The icebox took off, and there even was a market for harvested lake ice up until the 1930s. These required ice houses that kept the ice together even during the summer months until the lakes started freezing over again.

Nowadays we have refrigeration, which is possibly why Gormánuður may be puzzling to some of you. After all, we can get meat year round and keep it in the freezer or refrigerator. And you’re probably quite aware that our ancestors didn’t have refrigeration until 1913–not that long ago–available for home use. Even then, owning a home refrigerator was expensive and it didn’t become popular until the 1930s. So, your recent ancestors probably had iceboxes–that is actual boxes that held ice to keep their food fresh. The icebox was invented and patented by a farmer in 1802. The original icebox was made from wood, rabbit skins, and lots of ice (duh!). The icebox took off, and there even was a market for harvested lake ice up until the 1930s. These required ice houses that kept the ice together even during the summer months until the lakes started freezing over again.